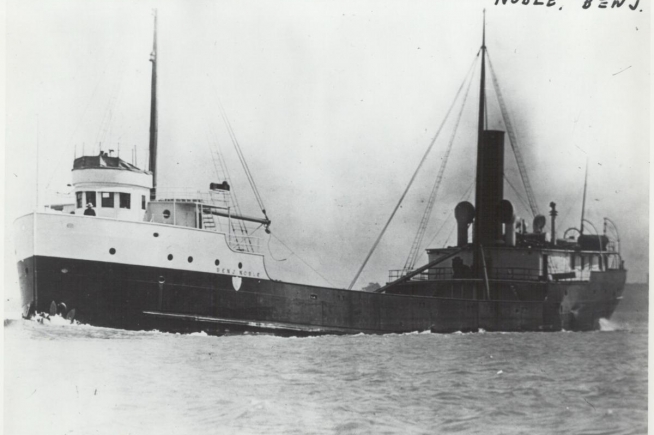

Benjamin Noble – Canaller Bulk Steamer 1909 – 1914 (SHIPWRECK)

Benjamin Noble – Canaller Bulk Steamer 1909 – 1914 (SHIPWRECK)

knife island MN

Found in 2004! The blockbuster announcement of the year for 2004 was the probable discovery of the long lost steamer Benjamin Noble. In 1914, she sailed through a crack in the Lake somewhere between Duluth and Two Harbors, taking 22 souls with her. She was found only a week before the Gales of November conference and the group brought the house down with their surprise announcement, which feature drop camera footage. The wreck lies in well over 300 ft of water and appears to have met a violent end, gouging out a deep crater when she struck bottom. Her triple steam whistle lies in the mud on her side and strongly suggests her identity as the Noble. It is also highly unlikely that any other large steel steamer lies in the area where she was found. Congratulations to Ken, Jerry, Randy, Craig and the other GLSPS members who spent innumerable hours scanning that vast lake bottom.

About The Benjamin Noble and Her Disappearance. In 1914 the Capitol Transportation Company owned one ship, the canaller Benjamin Noble. Hull number 206240 was built in 1909 in Wyandotte, Michigan and named Benjamin Noble after one of the CTC primary investors. Like the later Kamloops, she was called a canaller because of her 239 foot length, which meant the ship was short enough to pass through the locks of the Welland Canal. The Welland Canal and locks connect Lake Ontario and Lake Erie bypassing Niagara Falls. The Noble was built with a low cargo deck to facilitate loading deck cargos. Unlike most lakes freighters her stern cabins were elevated on a poop deck. Her bow cabins likewise were elevated on a forecastle deck. This made the Benjamin Noble somewhat unique in terms of lakes freighters. It also meant that her cargo deck sat very low in the water and was probably often awash. The other unique piece of the Noble construction was the way her bulwark or rails surrounded her cargo deck. They were solid sides built with large scuppers to drain water off the deck. This design also meant water could be trapped on the deck potentially making the ship more prone to rapidly taking on water if a hatch cover failed. In 1914 the country was in a major economic recession. Great Lakes freight business was slow and Mr. Francombe, the owner of CTC underbid a contract to carry railroad rails from Ashtabula, Ohio to Duluth. To avoid losing money on the contract the shipment had to be moved in one trip. Master of the Benjamin Noble was Captain John (Johnny) Eisenhardt, a young well-liked captain that had grown up on the lakes. The newly married Captain Eisenhardt was thirty-one years old, the youngest captain on the lakes and the Noble was his first commission. Delivering the load of rails was the first trip of the season and his first trip as a captain. He watched for six days as they loaded the rails one by one into the hold of his ship – the ship sinking deeper and deeper into the water with each rail. As a new captain it would have been difficult to stop the loading or refuse to take the load without jeopardizing his career. There were no Coast Guard regulations in those days to keep a ship from leaving port so grossly overloaded. The master was solely responsible for the safety of the ship. So overloaded was the Noblethat the anchors were partially submerged when they departed. Even so they could not fit the final two railroad cars of rails into the holds of the Noble and left them at the dock. None of the crew refused to sail on the Noble that April day. They new if they did, there was a line of sailors without jobs waiting to take their place. As amazed dockworkers watched her depart, Captain Eisenhardt assured them he would hug the shore all the way to Duluth to avoid any weather. The plan worked until he rounded Devil’s Island where Mother Superior had brewed-up a northeast storm from which there was no lea in this part of the lake. What happened after he altered course for Duluth can only be surmised. Overloaded, the maximum speed of the Noblewas likely only eight knots. At that speed, waves would have been breaking over his stern potentially flooding the cargo deck and increasing the grossly overloaded condition. In the midst of the blinding snowstorm, crewmen on two other ships thought they saw his lights disappear that night but didn’t know if it was the visibility or trouble. One sailor thought he saw the Noble turn into the seas before losing sight of her. Reports in the papers were equally confusing. One woman claimed she saw the Noble make it to Duluth and turn around because one of the entry lights was out. The lighthouse keeper in Two Harbors claimed he twice waved-off an unidentified ship that was trying to enter the shelter of the harbor. In the morning hatch covers, rafts, and other debris washed ashore at Park Point all from the Noble. Most of the conflicting stories were sorted out in the inquiry that followed. The evidence supported the theory that it never made Duluth or Two Harbors and sank somewhere off Knife River in the night before the storm reached its peak.

Current Status

Discovery Article

Superior Trips History Article

MN historical Society Shipwreck Map

All Content the property of MN Historical Societ, Great Lakes Shipwreck Research, and Superior Trips LLC.